A Patient's Guide to Biceps Tendonitis

Introduction

Biceps tendonitis, also called bicipital tendonitis, is inflammation in the main tendon that attaches the top of the biceps muscle to the shoulder. The most common cause is overuse from certain types of work or sports activities. Biceps tendonitis may develop gradually from the effects of wear and tear, or it can happen suddenly from a direct injury. The tendon may also become inflamed in response to other problems in the shoulder, such as rotator cuff tears, impingement, or instability (described below).

This guide will help you understand

- what parts of the shoulder are affected

- the causes of biceps tendonitis

- ways to treat this problem

Anatomy

What parts of the shoulder are affected?

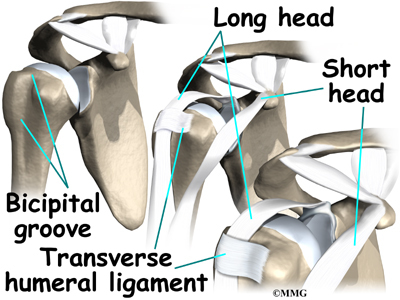

The biceps muscle goes from the shoulder to the elbow on the front of the upper arm. Two separate tendons (tendons attach muscles to bones) connect the upper part of the biceps muscle to the shoulder. The upper two tendons of the biceps are called the proximal biceps tendons, because they are closer to the top of the arm.

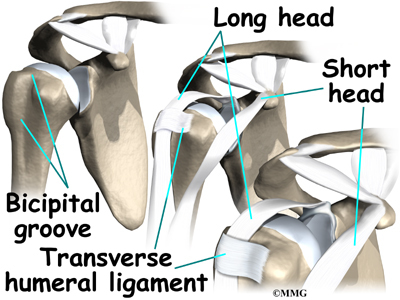

The main proximal tendon is the long head of the biceps. It connects the biceps muscle to the top of the shoulder socket, the glenoid. It also blends with the cartilage rim around the glenoid, the labrum. The labrum is a rim of soft tissue that turns the flat surface of the glenoid into a deeper socket. This arrangement improves the fit of the ball that fits in the socket, the humeral head.

Beginning at the top of the glenoid, the tendon of the long head of the biceps runs in front of the humeral head. The tendon passes within the bicipital groove of the humerus and is held in place by the transverse humeral ligament. This arrangement keeps the humeral head from sliding too far up or forward within the glenoid.

The short head of the biceps connects on the coracoid process of the scapula (shoulder blade). The coracoid process is a small bony knob just in from the front of the shoulder. The lower biceps tendon is called the distal biceps tendon. The word distal means the tendon is further down the arm. The lower part of the biceps muscle connects to the elbow by this tendon. The muscles forming the short and long heads of the biceps stay separate until just above the elbow, where they unite and connect to the distal biceps tendon.

Tendons are made up of strands of a material called collagen. The collagen strands are lined up in bundles next to each other. Because the collagen strands in tendons are lined up, tendons have high tensile strength. This means they can withstand high forces that pull on both ends of the tendon. When muscles work, they pull on one end of the tendon. The other end of the tendon pulls on the bone, causing the bone to move.

Contracting the biceps muscle can bend the elbow upward. The biceps can also help flex the shoulder, lifting the arm up, a movement called flexion. And the muscle can rotate, or twist, the forearm in a way that points the palm of the hand up. This movement is called supination, which positions the hand as if you were holding a tray.

Related Document: A Patient's Guide to Shoulder Anatomy

Causes

Why is my biceps tendon inflamed?

Continuous or repetitive shoulder actions can cause overuse of the biceps tendon. Damaged cells within the tendon don't have time to recuperate. The cells are unable to repair themselves, leading to tendonitis. This is common in sport or work activities that require frequent and repeated use of the arm, especially when the arm motions are performed overhead. Athletes who throw, swim, or swing a racquet or club are at greatest risk.

Years of shoulder wear and tear can cause the biceps tendon to become inflamed. Examination of the tissues in these cases commonly shows signs of degeneration. Degeneration in a tendon causes a loss of the normal arrangement of the collagen fibers that join together to form the tendon. Some of the individual strands of the tendon become jumbled due to the degeneration, other fibers break, and the tendon loses strength. When this happens in the biceps tendon, inflammation, or even a rupture of the biceps tendon, may occur.

Related Document: A Patient's Guide to Rupture of the Biceps Tendon

Biceps tendonitis can happen from a direct injury, such as a fall onto the top of the shoulder. A torn transverse humeral ligament can also lead to biceps tendonitis. (As mentioned earlier, the transverse humeral ligament holds the biceps tendon within the bicipital groove near the top of the humerus.) If this ligament is torn, the biceps tendon is free to jump or slip out of the groove, irritating and eventually inflaming the biceps tendon.

Biceps tendonitis sometimes occurs in response to other shoulder problems, including

- rotator cuff tears

- shoulder impingement

- shoulder instability

Rotator Cuff Tears

Aging adults with rotator cuff tears also commonly end up with biceps tendonitis. When the rotator cuff is torn, the humeral head is free to move too far up and forward in the shoulder socket and can impact the biceps tendon. The damage may begin to weaken the biceps tendon and cause it to become inflamed.

Related Document: A Patient's Guide to Rotator Cuff Tears

Shoulder Impingement

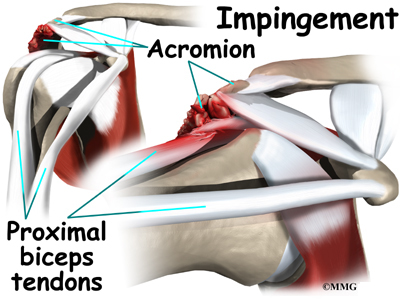

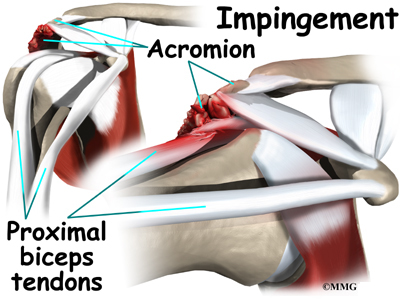

In shoulder impingement, the soft tissues between the humeral head and the top of the shoulder blade (acromion) get pinched or squeezed with certain arm movements.

Related Document: A Patient's Guide to Shoulder Impingement

Shoulder Instability

Conditions that allow too much movement of the ball within the socket create shoulder instability. When extreme shoulder motions are frequently repeated, such as with throwing or swimming, the soft tissues supporting the ball and socket can eventually get stretched out.

Related Document: A Patient's Guide to Shoulder Instability

The labrum (the cartilage rim that deepens the glenoid, or shoulder socket) may begin to pull away from its attachment to the glenoid. A shoulder dislocation can also cause the labrum to tear. When the labrum is torn, the humeral head may begin to slip up and forward within the socket. The added movement of the ball within the socket (instability) can cause damage to the nearby biceps tendon, leading to secondary biceps tendonitis.

Related Document: A Patient's Guide to Labral Tears

Symptoms

What does biceps tendonitis feel like?

Patients generally report the feeling of a deep ache directly in the front and top of the shoulder. The ache may spread down into the main part of the biceps muscle. Pain is usually made worse with overhead activities. Resting the shoulder generally eases pain.

The arm may feel weak with attempts to bend the elbow or when twisting the forearm into supination (palm up). A catching or slipping sensation felt near the top of the biceps muscle may suggest a tear of the transverse humeral ligament.

Diagnosis

How can my doctor be sure I have biceps tendonitis?

Your doctor will first take a detailed medical history. You will need to answer questions about your shoulder, if you feel pain or weakness, and how this is affecting your regular activities. You'll also be asked about past shoulder pain or injuries.

The physical exam is often most helpful in diagnosing biceps tendonitis. Your doctor may position your arm to see which movements are painful or weak. Available arm motion is checked. And by feeling the biceps tendon, the doctor can tell if the tendon is tender.

Special tests are done to see if nearby structures are causing problems, such as a tear in the labrum or in the transverse humeral ligament. The doctor checks the shoulder for impingement, instability, or rotator cuff problems.

X-rays are generally not needed right away. They may be ordered if the shoulder hasn't gotten better with treatment. An X-ray can show if there are bone spurs or calcium deposits near the tendon. X-rays can also show if there are other problems, such as a fracture. Plain X-rays do not show soft tissues like tendons and will not show a biceps tendonitis.

When the shoulder isn't responding to treatment, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan may also be ordered. An MRI is a special imaging test that uses magnetic waves to create pictures of the shoulder in slices. This test can tell if there are problems in the rotator cuff or labrum.

Arthroscopy is an invasive way to evaluate shoulder pain that isn't going away. It is not used to first evaluate biceps tendonitis. It may be used for ongoing shoulder problems that haven't been found in an X-ray or MRI scan. The surgeon uses an arthroscope to see inside the joint. The arthroscope is a thin instrument that has a tiny camera on the end. It can show if there are problems with the rotator cuff, the labrum, or the portion of the biceps tendon that is inside the shoulder joint.

Treatment

What treatment options are available?

Nonsurgical Treatment

Whenever possible, doctors treat biceps tendonitis without surgery. Treatment usually begins by resting the sore shoulder. The sport or activity that led to the problem is avoided. Resting the shoulder relieves pain and calms inflammation.

Anti-inflammatory medicine may be prescribed to ease pain and to help patients return to normal activity. These medications include common over-the-counter drugs such as ibuprofen.

Doctors may have their patients work with a physical or occupational therapist. Therapists apply treatments to reduce pain and inflammation. When present, conditions causing the biceps tendonitis are also addressed. For example, shoulder impingement may require specialized hands-on joint mobilization, along with strengthening of the rotator cuff and shoulder blade muscles. Treating the main cause will normally get rid of the biceps tendonitis. When needed, therapists also evaluate the way you do your work or sport activities to reduce problems of overuse.

In rare instances, an injection of cortisone may be used to try to control pain. Cortisone is a very powerful steroid. However, cortisone is used very sparingly because it can weaken the biceps tendon, and possibly cause it to rupture.

Surgery

Patients who are improving with conservative treatments do not typically require surgery. Surgery may be recommended if the problem doesn't go away or when there are other shoulder problems present.

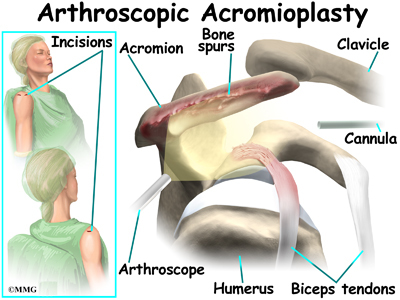

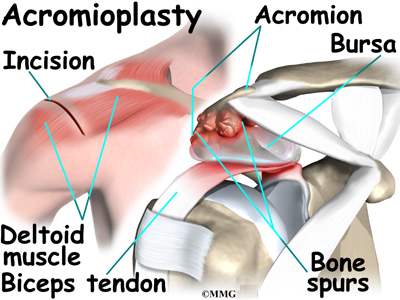

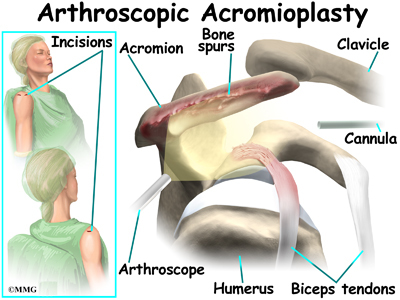

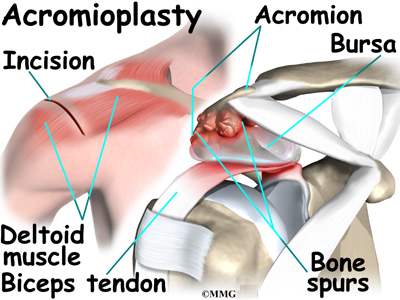

Acromioplasty

The most common surgery for bicipital tendonitis is acromioplasty, especially when the underlying problem is shoulder impingement. This procedure involves removing the front portion of the acromion, the bony ledge formed where the scapula meets the top of the shoulder joint. By removing a small portion of the acromion, more space is created between the acromion and the humeral head. This takes pressure off the soft tissues in between, including the biceps tendon.

Acromioplasty is usually done through a two-inch incision in the skin over the shoulder joint. In some cases, the surgery can be done using an arthroscope.

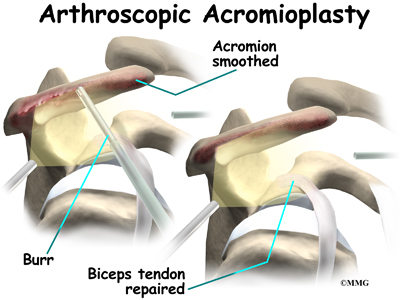

Today, acromioplasty is usually done using an arthroscope. An arthroscope is a slender tool with a tiny TV camera on the end. It lets the surgeon work in the joint through a very small incision. This may result in less damage to the normal tissues surrounding the joint, leading to faster healing and recovery.

To perform the acromioplasty using the arthroscope, several small incisions are made to insert the arthroscope and special instruments needed to complete the procedure. These incisions are small, usually about one-quarter inch long. It may be necessary to make three or four incisions around the shoulder to allow the arthroscope to be moved to different locations to see different areas of the shoulder.

A small plastic, or metal, tube is inserted into the shoulder and connected with sterile plastic tubing to a special pump. Another small tube allows the fluid to be removed from the joint. This pump continuously fills the shoulder joint with sterile saline (salt water) fluid. This constant flow of fluid through the joint inflates the joint and washes any blood and debris from the joint as the surgery is performed.

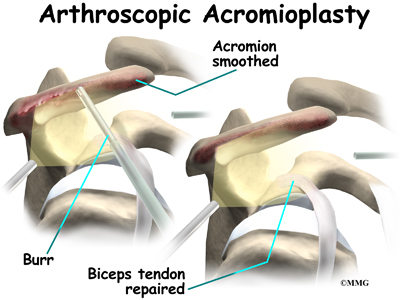

There are many small instruments that have been specially designed to perform surgery in the joint. Some of these instruments are used to remove torn and degenerative tissue. Some of these instruments nibble away bits of tissue and then vacuum them up from out of the joint. Others are designed to burr away bone tissue and vacuum it out of the joint. These instruments are used to remove any bone spurs that are rubbing on the tendons of the shoulder and smooth the under surface of the acromion and AC joint.

If necessary, the acromioplasty can also be performed using the older, open method. The open method requires a small incision in the skin over the shoulder joint.

Working through the incision, the surgeon locates the deltoid muscle on the outer part of the shoulder. Splitting the front section of this muscle gives the surgeon a better view of the acromion. Some surgeons also detach the deltoid muscle where it connects on the front of the acromion.

The bursa sac that lies just under the acromion is removed. Next, a surgical tool is used to cut a small portion off the front of the acromion. The ligament arcing from the acromion to the corocoid process (the coracoacromial ligament) may also be removed.

The surgeon shaves the undersurface of the acromion to remove any bone spurs. A file is used to smooth the edge of the acromion. Next, a series of small holes is drilled into the remaining acromion. These holes are used to reattach the deltoid muscle to the acromion.

The surgeon inspects the rotator cuff muscle to see if any tears are present. Then the entire area is irrigated to wash away small particles of bone. Finally, the free end of the deltoid muscle is sutured back to the ridge of the acromion using the drill holes made earlier.

If the biceps tendon is severely degenerated, the surgeon may perform biceps tenodesis (described next). The surgeon completes the procedure by closing the incision with sutures.

Biceps Tenodesis

Biceps tenodesis is a method of reattaching the top end of the biceps tendon to a new location. Studies show that the long-term results of this form of surgery are not satisfactory for patients with biceps tendonitis. However, tenodesis may be needed when the biceps tendon is severely degenerated or when shoulder reconstruction for other problems is needed.

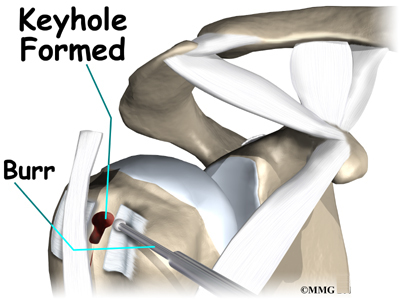

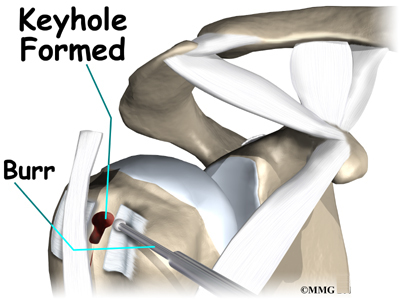

A common way to do this surgery is called the keyhole technique. The keyhole describes the shape of a small hole made by the surgeon in the humerus. The end of the tendon is slid into the top of the keyhole and pulled down to anchor it in place.

This surgery can be done using the arthroscope. The tenodesis procedure is usually combined with other procedures such as those discussed above. If so, the surgeon will simply continue using the arthroscope to do the tenodesis procedure if possible. The advantage of using the arthroscope is that less normal tissue is damaged. This may result in faster healing and recovery.

If the procedure is performed using the open method, the surgeon begins by making an incision on the front of the shoulder, just above the axilla (armpit). The overlying muscles are separated so the surgeon can locate the top of the biceps tendon. The end of the biceps tendon is removed from its attachment at the top of the glenoid. The tendon is prepared by cutting away frayed and degenerated tissue.

The transverse humeral ligament is split, exposing the bicipital groove. An incision is made along the floor of the bicipital groove. The bleeding from the incision gets scar tissue to form that will help anchor the repaired tendon in place.

A burr is used to form a keyhole-shaped cavity within the bicipital groove. The top of the cavity is round. The bottom is the slot of the keyhole. It is made the same width as the biceps tendon.

The surgeon rolls the top end of the biceps tendon into a ball. Sutures are used to form and hold the ball. The elbow is bent, taking tension off the biceps muscle and tendon. The surgeon pushes the tendon ball into the top part of the keyhole. As the elbow is gradually straightened, the ball is pulled firmly into the narrow slot in the lower end of the keyhole.

Rehabilitation

What should I expect after treatment?

Nonsurgical Rehabilitation

You will need to avoid heavy arm activity for three to four weeks. As the pain resolves, you should be safe to begin doing more normal activities.

Your doctor may prescribe a carefully progressed rehabilitation program under the supervision of a physical or occupational therapist. This could involve four to six weeks of therapy. At first, treatments are used to calm inflammation and to improve shoulder range of motion. As symptoms ease, specific exercises are used to strengthen the biceps muscle, as well as the rotator cuff and scapular muscles. Overhead athletes are shown ways to safely resume their sport.

After Surgery

Some surgeons prefer to have their patients start a gentle range-of-motion program soon after surgery. When you start therapy, your first few therapy sessions may involve ice and electrical stimulation treatments to help control pain and swelling from the surgery. Your therapist may also use massage and other types of hands-on treatments to ease muscle spasm and pain.

You will gradually start exercises to improve movement in the forearm, elbow, and shoulder. You need to be careful to avoid doing too much, too quickly.

Heavier exercises for the biceps muscle are avoided for two to four weeks after surgery. Your therapist may begin with light isometric strengthening exercises. These exercises work the biceps muscle without straining the healing tendon.

After two to four weeks, you start doing more active strengthening. As you progress, your therapist will teach you exercises to strengthen and stabilize the muscles and joints of the elbow and shoulder. Other exercises will work your arm in ways that are similar to your work tasks and sport activities. Your therapist will help you find ways to do your tasks that don't put too much stress on your shoulder.

You may require therapy for six to eight weeks. It generally takes three to four months, however, to safely begin doing forceful biceps activity after surgery. Before your therapy sessions end, your therapist will teach you a number of ways to avoid future problems.

|